The Biden administration is reportedly preparing to present a plan for vehicle fuel economy and emissions rules—potentially within the next week. And while the rules allegedly include steeper annual requirements and 40% of new-vehicle sales to be electric by 2030, environmental groups are stepping up to voice concerns that Biden’s plan might not be aggressive enough to make up for the Trump rollback.

Earlier this week the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) said that the new standards would need to reach a level of 55 miles per gallon equivalent, or 161 grams per mile, by 2026. That would make up for two things: the “near stagnation” in the standards for the 2021 and 2022 model years due to a Trump administration softening of standards to only a 1.5% annual increase, and the greater proportion of light trucks in the vehicle mix than when the Obama standards were written.

Under the Obama-era standards, with that vehicle mix, the fleet would be at a 47-mpg equivalent and 190 g/mi by 2026. The Trump EPA rules introduced in March 2020 carried over the existing framework of off-cycle credits, even though they did cut the annual fleet improvement from about 5% in Obama-era rules to just 1.5%. According to EPA data, in 2018 the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) requirement for automakers was 30.0 mpg, but the “real world” EPA fleet average mpg was 25.1 mpg.

2021 Toyota RAV4 Prime XSE

“Since the Obama standards were first introduced, technology has advanced rapidly with more affordable and high-performing hybrids and EVs,” wrote ACEEE senior research analyst Peter Huether on Monday. “We should not limit our ambition to the assumptions of 10 years ago when designing new standards.”

Heuther found that if the administration set standards that only reached the same fleetwide average as the Obama standards by 2026, it would recover just two-thirds of the emissions reductions that the uninterrupted Obama program would have.

Put generally, allowing two full model years of a dirtier fleet than had originally been intended has a lasting effect on the environment—a Trump legacy, if you will.

The off-cycle game

The concerns aired by environmental groups aren’t only focused toward the emissions targets themselves. Union of Concerned Scientists senior vehicles analyst Dave Cooke on Wednesday called for a review of “off-cycle credits”—referring to the credit system meant to incentivize technologies that might not provide acute advantages in the EPA’s test cycles but provide a advantages in real-world emissions and efficiency.

But with little or no accountability as to the emissions benefits of off-cycle technologies, UCS estimates that they cost 21 million tons of global warming emissions for vehicles sold from 2012-2019.

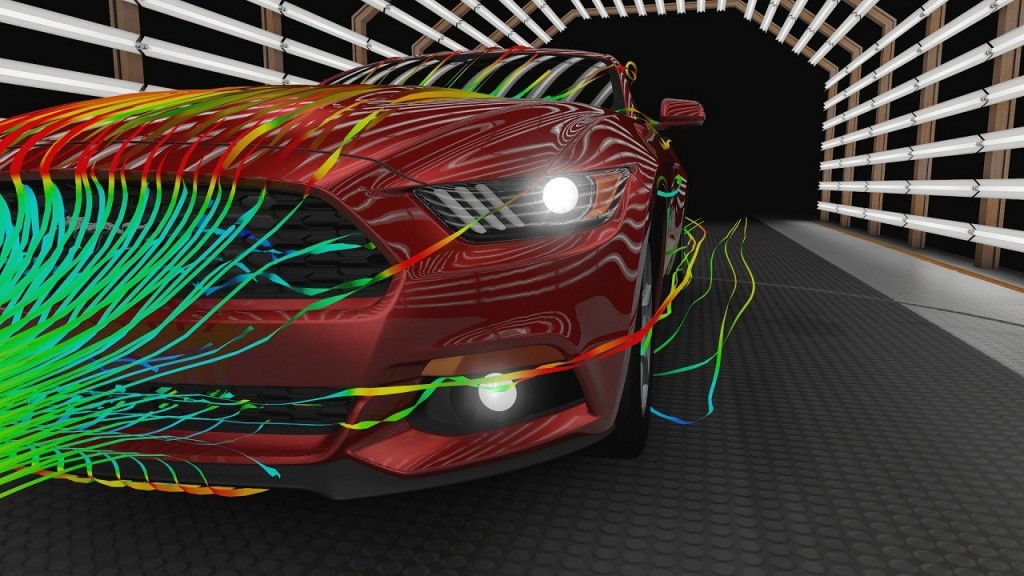

2015 Ford Mustang EcoBoost active grille shutters

One such example of an off-cycle credit that’s widely claimed is active grille shutters that open at lower speeds to provide more cooling but close at higher speeds to improve aerodynamics. Other examples include adjustable ride height, engine idle-stop systems, solar panels, waste-heat recovery systems, and items like “active transmission warm-up” that seem more related to longevity than to efficiency.

The credit program’s status as an incentive to spur adoption was even abused. The original intent was to apply credits to these technologies as they were added to vehicles, from 2014 on, Cooke explained. But instead automakers were claiming them for vehicles that had already been using them—and furthermore, the EPA started granting them retroactively, going back years.

Cooke makes clear that UCS isn’t convinced on the benefits of these credits to the fleet, as applied. He said: “Without doing anything new or novel, suddenly manufacturers were able to “achieve” between 9% and 19% of the total available credits!”

U.S. CO2 reduction and off-cycle credits - ICCT, 2018

As the ICCT reported in 2018, the use of off-cycle credits was expected to be an ever-greater portion of expected CO2 reductions—about 10% in 2020, up to about 18% in 2025.

It’s entirely possible for automakers who make only EVs to be negative-emissions on the EPA scale, by a shocking amount, because of off-cycle credits. According to the EPA, in 2019 Tesla achieved 0 g/mi tailpipe emissions, with an overall -22 g/mi due to 22 g/mi of air-conditioning and off-cycle credits. Considering the multiplier applied, Tesla’s “performance value” was at -236 g/mi.

2021 Tesla Model X

Companies typically bank credits—many from off-cycle claims—from year to year under the current CAFE standards, so that they might sell more low-mpg trucks. For the 2019 model year, all but Tesla, Honda, and Subaru used banked credits to lower their number below their calculated standard—considering vehicle footprint and the mix of cars and trucks.

Seemingly emboldened, automakers haven’t hesitated over the years to make some suggestions for additional off-cycle credits. In 2015 they proposed that they should receive fuel economy credits for building safer cars—with a version of the off-cycle credits awarded for things like lane departure prevention. Green Car Reports isn’t aware that there ever was research presented justifying the emissions benefits.

Audi e-tron, on the Golden Gate Bridge

Even recently, as Cooke underscores, automakers did get additional off-cycle perks. In the voluntary agreements that CARB made with automakers starting in August 2019, it boosted the cap for off-cycle credits by 50%. With federal rules due to more closely following California rules, that’s something that might be extended at the national level.

UCS calls for a reevaluation of the technologies on the off-cycle menu, with new credits only given to tech for which there are “clear and established test procedures and rigorous datasets rooted in direct A/B comparisons.” It also points out that there should be negative credits for automakers who get the credit for tech that isn’t proven to cut emissions.

Will the Biden administration rise to the challenge? The President’s climate goal requires a 50% to 52% reduction in emissions by 2030, the ACEEE underscores. To get there, new rules should require tighter targets, with some flexibility, but definitely fewer games.