Trains are about to go electric.

Battery-electric, that is. While electrical propulsion has been the preferred way to move trains for most of a century, the idea of moving them longer distances via battery is one that’s just now being realized.

Like long-range electric cars, it’s a reality afforded by the energy density and longevity of modern lithium-ion battery packs.

Simply put, the special trains allow some rail routes to go electric where it wouldn’t otherwise be possible.

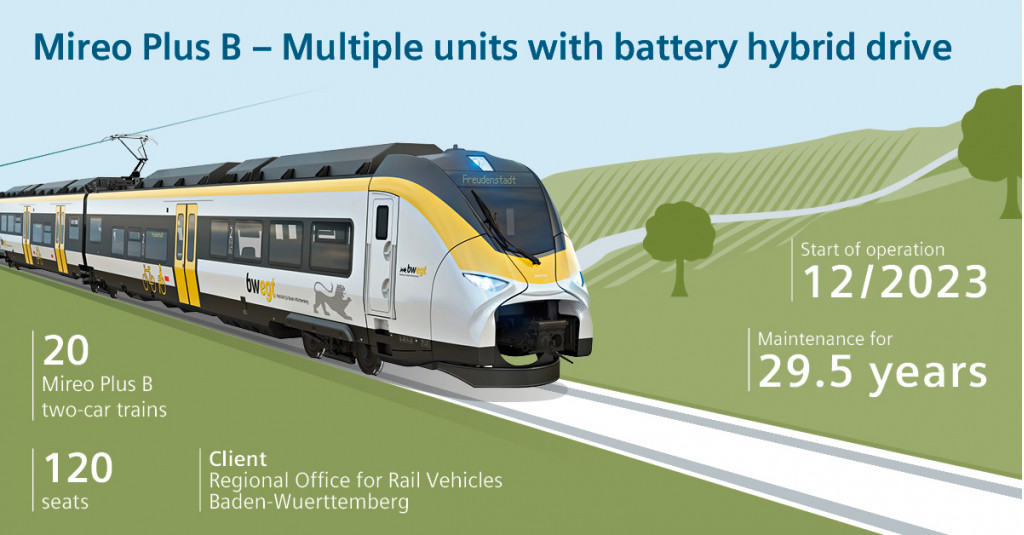

In Germany, where only about 40 percent of track is electrified, the trains will clean the air along routes that might have been impractical or prohibitively expensive to electrify, the state of Baden-Württemberg has ordered 20 two-car trains built in Germany by Siemens, who will oversee energy consumption and energy costs over a nearly 30-year service period.

It’s the first such order for battery-electric trains for Siemens Mobility, who will deliver them by June 2023. In them, a lithium-ion battery pack is mounted under the train’s floor and is charged while it moves along via overhead lines, using them to both power the train and charge the battery. When the train reaches a stretch of rail with no overhead lines, the battery takes over.

Siemens battery-electric train

The new trains are part of Siemens’ Mireo train platform for regional and commuter rail—boasting weight reductions and improved aerodynamics. Configurations range from two to seven cars, and top speed, depending on the version, ranges from 87 to 124 mph.

Germany and France are two markets that have started investing in battery-electric trains. Last month another company, Alstrom, announced that it has a first contract to supply battery-electric regional trains for Germany’s Leipzig-Chemnitz line with three-car trains that can cover up to 75 miles and reach a top speed of 99 mph.

That same company has tested hydrogen fuel-cell power as the alternate source instead of batteries. And the Canadian company Bombardier in 2018 launched the Talent 3, an electro-hybrid train that can cover up to 62 miles on non-electrified track, with a modular approach to configuring motors and batteries.

Two BNSF locomotives hauling coal trains meet near Wichita Falls, Texas

This is a great thing not only for those who live near high-traffic train tracks but for those who travel by train, because in addition to reducing the reliance on oil, there are some indications it can have a profound effect on health.

A Danish study last year found that traveling on a diesel train can expose you to higher levels of harmful ultrafine particulates than standing next to a busy highway. Researchers found six times the levels of black carbon and 35 times the levels of ultrafine particulates inside passenger trains pulled by diesel locomotives versus electric ones.

Holland still remains the leader for rail electrification; it powers 100 percent of its trains on sustainable energy—almost entirely wind power, buffered by energy storage systems.

GE Transportation battery-electric logomotive project

In the U.S., GE Transportation is working on a battery-electric locomotive, in partnership with BNSF, with a heavy-duty freight-train approach—packing in more than 2,400 kilowatt-hours and potentially going hundreds of miles on battery power.

Electrifying even passenger rail in America—or building new high-speed passenger-rail lines—poses a greater challenge than virtually everywhere else in the world with well-developed railroads. Most U.S. passenger rail lines are shared with freight, and according to the Environmental and Energy Study Institute, less than one percent of all rail miles in the U.S. are electrified, versus more than one-third of global trains.