Rivalry is a good thing. And the electric-car field doesn’t have near enough of it.

There’s a delightful start of some happening between Tesla and upstart Lucid, and it’s already shown through in fits and starts.

In September 2020, a few weeks after Lucid revealed preliminary range numbers of up to 517 miles for a top version of its Air, Tesla started accepting orders for a 520-mile version of the Model S Plaid—a version that might never have existed outside of a product map. It later was canceled.

Then a month later, in October, Lucid revealed a $77,400 starting price for the base version of the AIr, called Pure. Tesla CEO Elon Musk later the same day announced that the company would cut the price of its Model S by more than $5,500—effective that same night.

Lucid CEO Peter Rawlinson, who ten years ago coordinated the technology behind the Model S on the way to production, notes that Tesla is the only other company with a comprehensive approach toward efficient EVs right now.

Peter Rawlinson

As part of a wide and varied interview with Green Car Reports late last month, just after the commissioning of Lucid’s factory in Casa Grande, Arizona, Rawlinson explained that it’s one of the key differentiators that make Tesla and Lucid different from the rest. While most other automakers are merely making EVs, count Lucid among a much smaller group in which the tech leads the product.

“Maybe us...maybe we’ll push Tesla a bit,” he said with a playful look. “I think that would be great,”

Rawlinson also has an overarching plan that leads to much more than niche electric luxury sedans weighing well over two tons—however efficient they might be.

“What I will be proud of is if I can use this technology and the efficiency to drive down the cost so that the man on the street could afford an electric car,” he said. “Tesla’s doing that, and hats off to Tesla for doing it; but right now it’s a one-horse race, it’s bloody ridiculous.”

Lucid CEO Peter Rawlinson - Arizona plant commissioning

Efficiency is the single most relevant metric related to EVs and how they succeed, and it defines the prowess of an EV company, according to Rawlinson, who at a speech at the plant last month, with Arizona Governor Doug Ducey, focused in on how Lucid had accomplished more than 4.6 miles per kilowatt-hour in a production model. That's far more than the Tesla Model S, and bested only by the base Model 3 Standard Range Plus, which Tesla says is at 5.1 miles/kwh in its latest Impact Report.

On the way to affordability

Far down the line from the stunning Air sedan, which debuts in $169,000 Dream Edition form, Rawlinson sees a mass-market, $25,000 EV with a 150-mile EPA range from a 25-kwh battery pack as something its business plan might potentially lead to late in the decade—if the charging infrastructure is robust and more people can charge overnight. (Push back here: who wanted that when it was called a Leaf?)

“Six miles per kilowatt hour, 150 mile range, in a 25 kilowatt hour pack,” he summed decisively. A $25,000 EV is something Tesla CEO Elon Musk announced last year, due in 2023 on notoriously optimistic timelines, so perhaps such projects might be future rivals.

Taking a step back to why the Air flagship is first up, Rawlinson is ready with a rebuttal: “I hear all these cries for ‘Well, it’s another rich man’s car,’ but the pragmatist in me knew that we had to do this first step.”

Lucid Air in production - Casa Grande, Arizona

The cost of industrializing a product is almost inversely proportional to the cost of the product, he explained. So, for instance, it would cost many times as much to create an affordable mass-market car.

“If my passion is the world needs a $25,000 EV, there’s no way I could do that because I’d have to go and get $15 billion, not $1.5 billion, to industrialize it,” Rawlinson said.

At 520 miles, Air defines the brand

“And then there’s another reason, that the first product defines the brand—so you want to go from high-end technological tour de force. How did the iPhone succeed, how did Dyson succeed, how did Lexus succeed with LS400?”

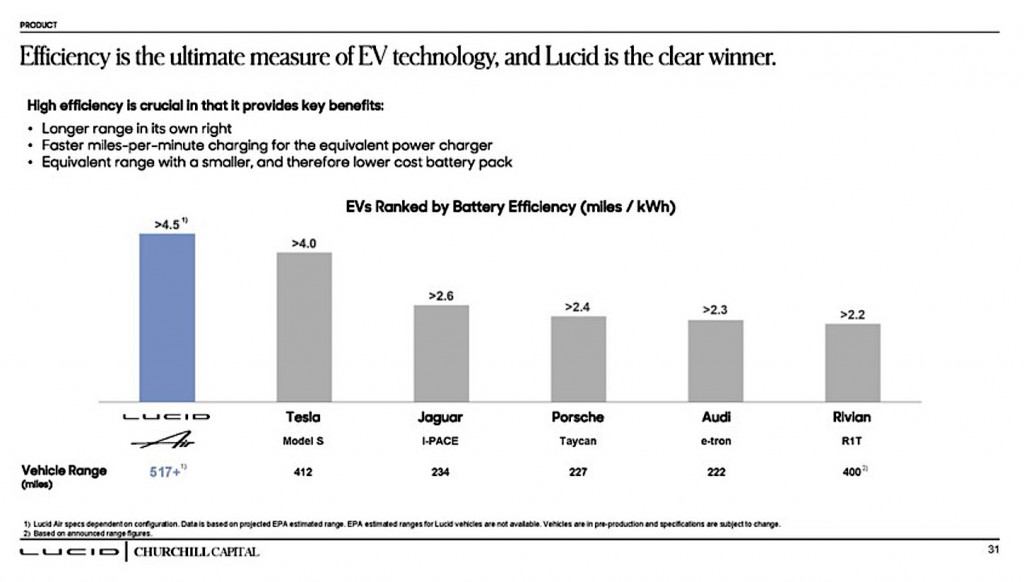

Lucid efficiency - Lucid Motors investor presentation filed with SEC, July 2021

That hooks back to why Rawlinson is seemingly so obsessed with efficiency and the technology enabling it—because it enables an entire business model. Lucid Group will likely consist of three things—vehicles, energy storage, and technology. While the tech enables the first two, Lucid hasn’t shied away from the idea that it’s developed its core systems with crossover potential to other industries.

“What drives me is that the efficiency can be turned on its head, and we can use that as a positive,” the CEO added, bringing the conversation over to the Air electric car, which will be delivered later this month and then ramped up to include the entry Air Pure after a year or so. If the Lucid Air Pure covers its 408-mile estimated range with only about 88 kwh—roughly 13 kwh less than the closest competitor, Rawlinson quips, clearly pointing to Tesla—then it means carving out larger margins sooner.

And then what starts as a sort of “engineering purist play,” as he put it, jeering himself momentarily as a nerd, starts to look like smart business as production ramps up and Lucid, selling in higher numbers and using fewer cells to do it, has more flexibility to lower the price. As Lucid’s CEO and CTO, Rawlinson wears both caps well.

Working its way toward affordable and mass-produced

As it launches the Air, Lucid is working on its seven-passenger Gravity SUV, due in 2023 and enabled by the company’s Phase 2 expansion—to a 53,000-vehicle capacity from the current 34,000-unit capacity. And then the third step, perhaps as soon as 2025 according to an investor presentation earlier this year, will be to apply the company’s tech approach to a Tesla Model 3/Model Y type vehicle—with an expansion of the plant extending it out to a 365,000-unit planned annual capacity.

Lucid Project Gravity - from video clip during Air debut

Lucid aims to make about three million Air and Gravity models over the next decade, with its product family by 2030 potentially including a pickup and coupe.

Rawlinson said he’s accustomed to a question regarding competition and how there can be a market for this number of EVs. “And I always say there’s no such thing as a market for EVs, only cars, and the market penetration for EVs is tiny. So I’m going after the remaining 97%. Why would I go after the 3%? I think it’s the most ridiculous construct.”

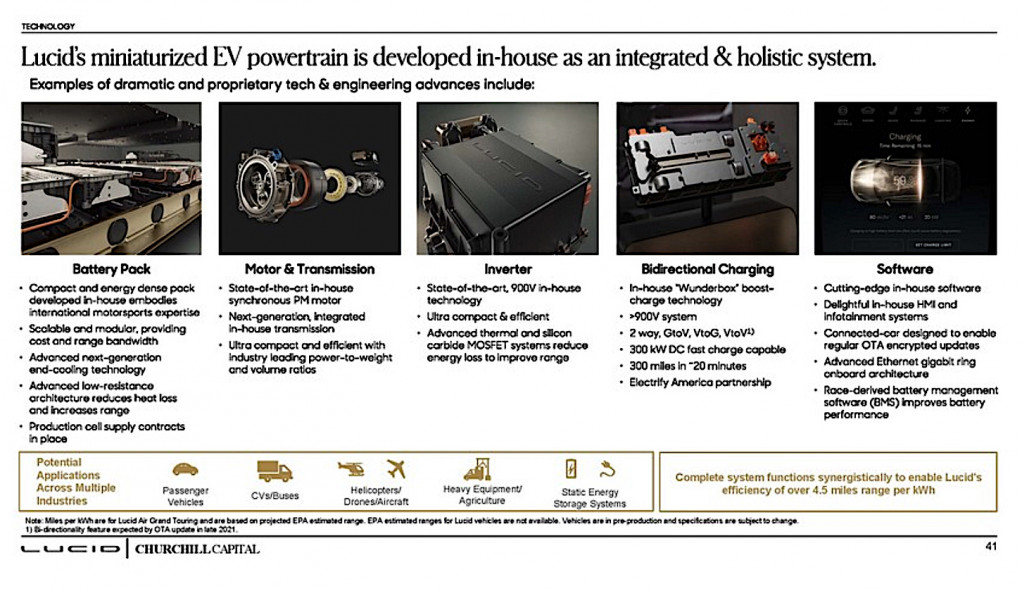

To get to the $25,000 EV, Rawlinson thinks that the industry is a little too focused on batteries and not enough on other aspects like efficiency and charging—partly why it's put its development resources toward a full propulsion and charging suite but not batteries.

Lucid propulsion - Lucid Motors investor presentation filed with SEC, July 2021

“The point is that we need to mass-industrialize cells to drive the cell price down, we need a more mature charging infrastructure, we need to push like crazy on efficiency,” he emphasized. “And then we think about the car of the future having less range—and then that's the inflection point to get to a $25,000 car, that's what I want to do.”

How far off is that project? “If Lucid was gonna do it, I think it’s about eight years away,” he said, remaining notably noncommittal. Although he quickly added that it could do a car in about three years’ time that could get six miles per kwh—perhaps a hint to the Model 3/Y rival. “What I don’t know is when we get cells down to $80 per kilowatt-hour...and what I don’t know is the human psyche, about the fast-charging infrastructure and how palatable that’s going to be.”

Range isn’t everything, says the company with the most range

Which gets to the point: The CEO of the electric car with the longest EPA-rated range ever isn’t convinced that range is ultimately what matters.

“I do think that the electric car of the future will have less range, paradoxically,” he reiterated. “And the future antidote for range anxiety will be a more mature and built-out infrastructure. Why haven’t I got gasoline range anxiety? Because I know there’s a gas station on every street corner.”

Lucid Air Dream Edition

Rawlinson suggested that over time Lucid’s efficiency advantage could overcome some areas seen as insurmountable Tesla strengths—like charging. Lucid has, instead of building out a DC fast-charging network, as Tesla did a decade ago, partnered with VW’s Electrify America.

Vs. Tesla, the second-mover advantage

“I see it as a second-mover advantage. Because Tesla had to put it out there; they were at the forefront; they were the vanguard. Now they did so at 400 volts because that was the voltage of Model S. And it’s hugely capital-intensive.”

“That was the right solution for Model S; it probably wasn’t the right solution for the Supercharger network,” Rawlinson opined.

Tesla Supercharger V3 station - Las Vegas Strip

It’s better to put the investment into tech and manufacturing, he argues. “I believe passionately that we have to be vertically integrated to manufacture in-house; I don’t believe in the asset-light manufacturing model as some startups subscribe to,” he said, referring to the plans some have of buying key propulsion tech from suppliers and contract-manufacturing vehicles. “Going asset-light with the charging infrastructure, but capital-intensive, total-focused on manufacturing: That’s the combination.

“Let me tell you, the EVs of the future will be ultra high-voltage,” said Rawlinson who, from the sheer physics of going with a 924V system in the Air versus Tesla’s 400V, called it “an inherent advantage.”

Is this the start of a healthy rivalry? Like Ford and Chevy and their arms race over payloads and towing, an arms race over efficiency, between two American car companies, might well be what we need.