This past winter’s deep freeze and its record-low temperatures exposed a reality that anyone thinking about an electric car has to come to terms with: Cold winter weather can cut the effective driving range of some electric vehicles by 40 percent or more.

Partly to blame is that the resistive heating electric cars rely on (yes, like those glowing elements in your toaster) takes a lot of energy. But it’s more than that, as the batteries themselves need to be warmed to be at their best.

The supplier Mahle is one of several companies looking at the cold-weather problem comprehensively. Last month it announced what it calls the Integrated Thermal System, which the company says could recover 20 percent of the cold-weather loss.

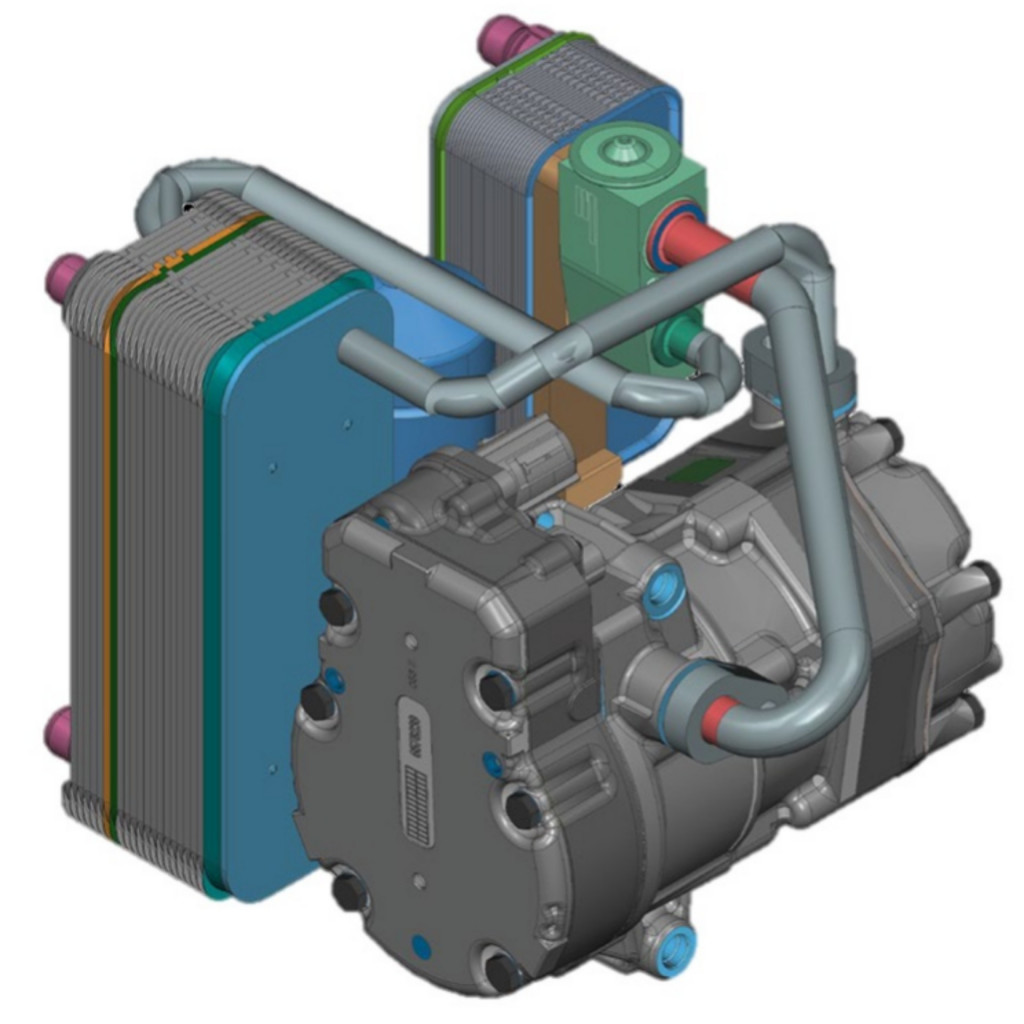

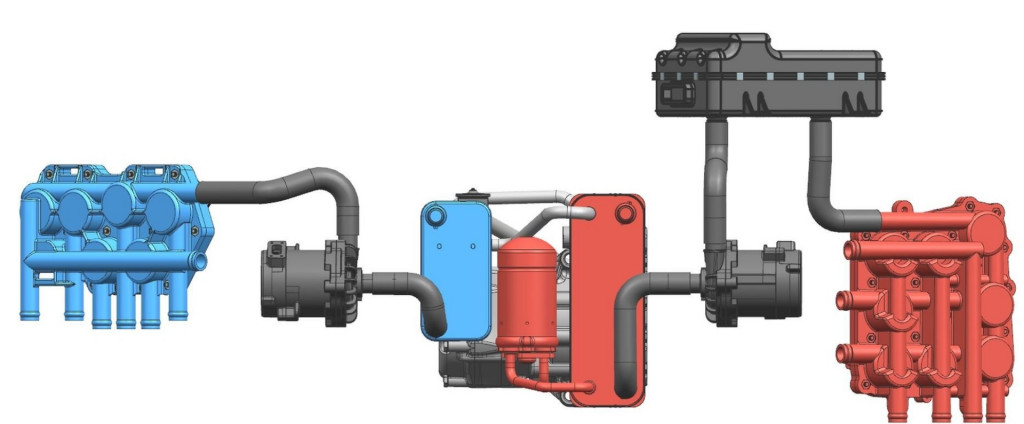

Mahle Integrated Thermal System

That system is one of several developed by suppliers around heat-pump technology and other thermal strategies, aiming to reduce the load on resistive heating.

Heat pumps aid efficiency because they move heat rather than generate it. Models with heat pumps typically use a reversible setup to transfer thermal energy out of the cabin during hot weather (functioning as an air-conditioning compressor), and to bring thermal energy from power components or outside into the cabin in cold weather. According to Bosch, a heat pump drawing 1 kw will generate the heat equivalent of between 2 and 3 kw.

Climate control systems still need the toaster bits and the traditional air conditioning operation for quick heat or cooling when you get in the car, but they help keep things comfortable over long commutes or road trips.

![2017 BMW i3 electric car during winter snow storm [photo: owner Chris Neff] 2017 BMW i3 electric car during winter snow storm [photo: owner Chris Neff]](https://images.hgmsites.net/lrg/2017-bmw-i3-electric-car-during-winter-snow-storm-photo-owner-chris-neff_100596469_l.jpg)

2017 BMW i3 electric car during winter snow storm [photo: owner Chris Neff]

The 2013 Nissan Leaf was the first mass-produced vehicle in the world to offer a heat-pump-based cabin heater; that system has helped extend driving range during the winter months. All versions of the BMW i3 EV have offered it, and the Jaguar I-Pace and Audi E-tron have a heat-pump system. So does the Toyota Prius Prime, and most versions of the Volkswagen e-Golf.

Not all EVs have it. The Hyundai Kona Electric doesn’t come with a heat pump while the Kia Niro EV does. Tesla models don’t use a heat pump as part of the climate control system but do use waste heat from the motor and power electronics to help warm the battery.

2019 Kia Niro EV first drive - Santa Cruz, CA - February 2019

The Mahle ITS incorporates several different components into a single system that can help with heating and cooling, for both the cabin and power systems. A chiller and condenser serve the functions of an evaporator and condenser, while in between there’s a thermal expansion valve and at the other end of the system, an electric drive compressor.

What makes it different is that it’s a neatly packaged, modular system that “can be adapted to future vehicle architectures,” Mahle says, and a unified alternative to what the supplier originally teased as a “holistic thermal management” system in 2017.

Mahle Integrated Thermal System

With Tesla the one exception, perhaps, EVs that omit the heat pump in the climate system generally do so to save cost. Climate control systems that take full advantage of heat-pump systems increase the vehicle’s cost by a few hundred dollars, we’ve been told, while resistive heat is cheap.

There’s another reason why many more vehicles don’t have it—especially in the U.S. A heat pump system won’t raise official range estimates significantly, if at all. Heating especially gets skipped over in the EPA’s driving-cycle calculations for EVs. (There’s currently a hot-weather air-conditioning cycle for gasoline and diesel vehicles).

The gains are significant, though. Visteon (now Hanon Systems) claimed some years ago that in a New York City drive cycle, at 14 degrees, its fully developed heat-pump-based system offers up to a 30 percent improvement in driving range. And with a smart thermal management system that Bosch introduced in 2015, it claimed 25 percent better range in wintry urban situations.

To that, there’s some cost-benefit analysis to be done. Heat pumps don’t solve the cold-weather range punch, but they do soften the blow. Spending on a heat pump will save many kwh of energy, and that translates directly to more miles of range (or less battery capacity needed)—meaning you recover more miles per minute you’re fast charging.

For electric cars that are truly intended for use outside of California—and ready for next year’s deep freeze—the tech is becoming harder to ignore.