Eight years ago, ethanol was going to let the U.S. grow its own vehicle fuel, reduce its use of gasoline made from imported oil, and boost energy security.

How much have you heard about those themes lately? Not much, we'd wager.

A lot has changed since the 2007 passage of the Energy Independence and Security Act, which set volume requirements for biofuels to be blended into U.S. fuel supplies.

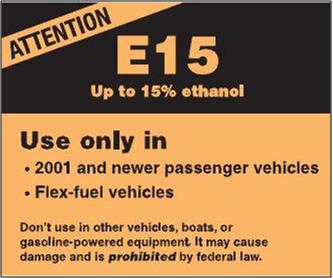

Proposed EPA E15 gasoline pump warning label for ethanol content

A high-level look at the current state of ethanol, in a Navigant Research blog post, suggests that ethanol has fallen victim to several forces that have combined to reduce the need for the volumes specified almost seven years ago.

What a difference

U.S. domestic natural-gas production has soared, and the price of the fuel has fallen substantially, making it more attractive as a substitute for other industrial fuels--including oil.

Under the Obama Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency has moved slowly toward greater regulation of carbon emitted by the domestic electric-utility industry.

And Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) rules have been put in place covering vehicles through the 2025 model year, making standards clear for automakers selling in the U.S.

Highest-ever MPG

The average fuel economy of new cars sold has never been higher. It's now almost at 25 mpg across all vehicles, weighted by sales volume. Meanwhile, plug-in electric vehicles use no gasoline at all.

Paradoxically, the economic recession actually helped, delaying replacement of some vehicles until after more stringent CAFE rules came into effect. U.S. drivers also have fewer cars, and are driving them less.

The net result is that the U.S. energy picture is vastly different than it was a decade ago, shortly after the 9/11 attacks.

But the 2007 Energy Security Act was drafted under the assumption that U.S. gasoline consumption would continue to rise.

![Renewable Fuel Standard credits earned [U.S. Energy Information Administration] Renewable Fuel Standard credits earned [U.S. Energy Information Administration]](https://images.hgmsites.net/med/renewable-fuel-standard-credits-earned-u-s-energy-information-administration_100449147_m.jpg)

Renewable Fuel Standard credits earned [U.S. Energy Information Administration]

The denominator problem

So the Act mandated specific volumes of biofuels to be used in U.S. vehicle fuel: The curent goal is to use 36 billion gallons of renewable fuels by 2022.

In May, the U.S. Energy Information Administration said in a Market Trend report that biofuel consumption "falls well short" of that target.

In fact, U.S. gasoline usage peaked in 2006--the year before the Act was passed--and has fallen steadily since then.

Here's the problem: If miles driven and car sales are essentially flat--the U.S. market averages 14 to 15 million vehicles a year--and fuel efficiency rises steadily, that means less fuel will be consumed.

Which, in turn, means that the biofuel volume goal becomes a larger percentage of total fuel supplies than it would have been in 2007.

It's called "the denominator problem"--you're dividing by a smaller number--and it's the source of much pain for the EPA.

Dialing down ethanol

That's why the agency called last month for a 20-percent cut in the volume of ethanol mandated to be added into the fuel supply for 2014.

No doubt the agency is also quite aware of the controversy around its June 2012 increase in the permissible ethanol level in gasoline--from E10 to E15, or a blend of 15 percent ethanol and 85 percent gasoline.

Pump with multiple ethanol/gasoline blends.

The AAA has come out against E15--as have a number of other groups--claiming that only 5 percent of light-duty vehicles on U.S. roads can presently use the fuel. The EPA says E15 can be used in cars built in 2001 or later.

(Meanwhile, biodiesel makers beg the EPA to distinguish between ethanol and renewable diesel fuel.)

The transition to more ethanol has been slow to roll out, in part because gas stations must buy expensive new "blender pumps" to adjust ethanol levels for each fill-up.

Percents, not gallons?

Our inner mathematician suggests that rather than numeric volume targets, it might have been sounder public policy to set the mandate as a percentage of total vehicle fuel.

That brings its own challenges, of course. A volume mandate at least lets ethanol refineries know how much of their product is required by law.

At least, that is, until the rules change.

How do you handicap ethanol's chances over the next 10 years?

Leave us your thoughts in the Comments below.

_______________________________________________