Sometimes even well-informed industry analysts get it wrong. Or miss the forest for the trees.

A recent posting by Pike Research, entlted "Europe Leads, U.S. Lags In Start-Stop Hybrids," correctly notes that adoption of start-stop systems is well advanced in Europe, but lags behind in the U.S. But it fails to explain why that's the case.

U.S. makers unwilling?

The Pike Research piece says:

This is likely to be another unfortunate example of auto makers only reducing emissions when pushed .... Stop-start hybrids won’t likely invade our shores until ... rising MPG fuel economy standards push auto makers to consider adding this relatively inexpensive technology.

2011 Mazda2 First Drive

What is start-stop?

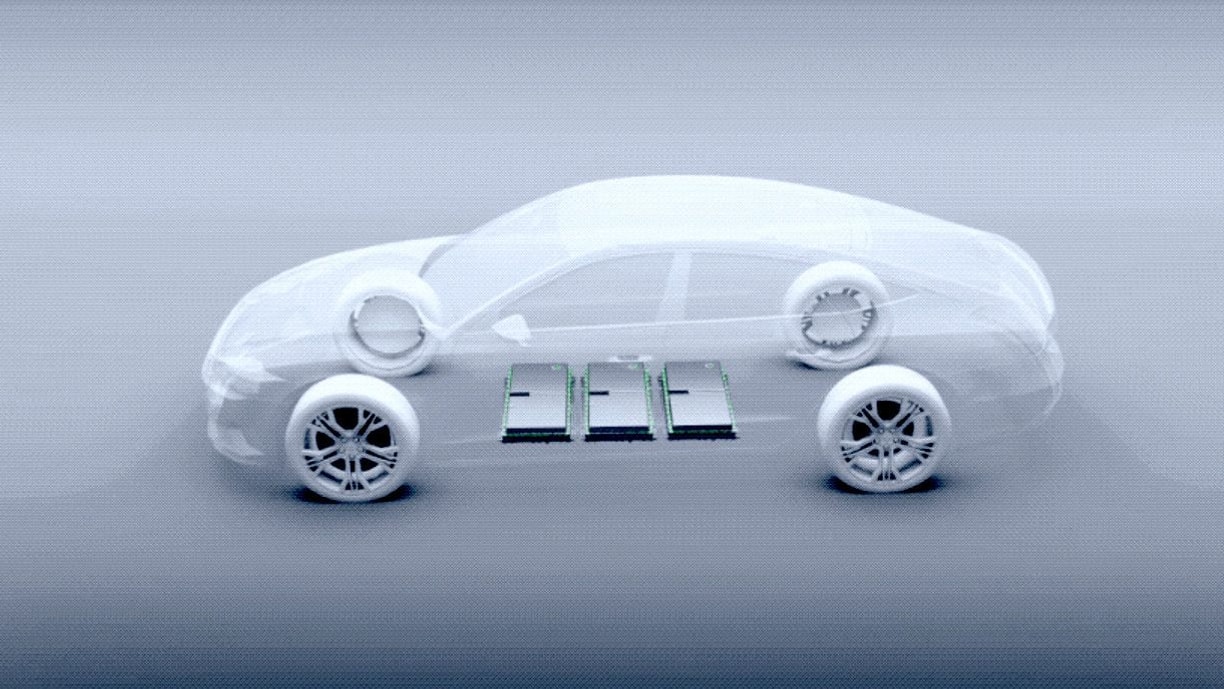

A start-stop system switches off the engine when a car stops. As the driver begins to lift a foot off the brake or clutch pedal, the system quickly restarts the engine, usually with a beefed-up 12-Volt starter battery.

Start-stop systems are sometimes called "micro-hybrids," but we don't use that term because they don't have the separate battery packs or high-voltage electric components that define a hybrid-electric vehicle.

If start-stop systems so clearly cut consumption, why wouldn't U.S. makers adopt them? The answer is simple: Differing duty cycles and emissions-test procedures.

More suburbs, fewer Manhattans

Like full hybrids, start-stop systems produce best results in heavily congested urban stop-and-go traffic, where cars spend long periods stopped. Think Tokyo, or Manhattan. While start-stop systems can't move the car on electricity alone, they keep the engine off for multiple stop light cycles or standstills.

In American suburban sprawl, cars may accelerate from a stop to 50 mph, travel several miles, then stop briefly at a single light before perhaps making a right on red into the mall parking lot.

2011 Mazda2 exterior and detail

Suburban drivers get stuck in traffic too, but they rarely sit still for several minutes. Even the notorious LA freeway congestion rarely stops dead that long. Instead, brief halts are mixed with speeds from 10 to 80 mph, all requiring the engine to stay on.

From emissions comes mileage

The EPA fuel-economy ratings for every new car sold in the U.S. are actually derived from its emissions testing. Exhaust gases are gathered in huge bags when cars go through a defined and well-known cycle of acceleration, coasting, braking, etc.

From the volume and content of emitted exhaust gases, the EPA calculates gas mileage. And then it applies "adjustment factors" to make the results roughly match real-world mileage.

But on the EPA's increasingly unrealistic, 1970s-era test cycles, a start-stop system provides little benefit. The tests just don't include long enough stopping periods.

Projections of global hybrid-electric light-duty vehicle sales 2010-2015, by Pike Research

Just 0.1 mpg?

Robert Davis, senior vice-president for quality, research and development at Mazda, talked to us last year about the challenges facing the company's innovative iStop system. It's offered on the 2011 Mazda2 subcompact in other markets.

Under EPA test procedures, Davis said, iStop would raise the rating for city mileage no more than 0.1 or 0.2 miles per gallon. Mazda's projects that in heavy urban traffic, it cuts consumption as much as 8 percent--a boost of 3 mpg.

Chatting with the EPA

Mazda has discussed the start-stop issue with the EPA, Davis said. Their goal is to agree on additional tests and adjustment factors that spell out the mileage increase from a start-stop system in stop-and-go traffic.

The iStop system might be marketed for around $300 as as a mileage-boosting option in markets where cars spend lots of time idling at a dead stop. Those include cities in the Northeast Corridor, the densest areas of the Los Angeles Basin, and other heavily urbanized areas.

$300 for 3 MPG?

At that price, iStop's payback might prove better than that of full hybrids, which typically cost several thousand dollars more than the most efficient non-hybrid versions of the same model.

A final sticking point: EPA regulations require cars to perform a complex series of diagnostic checks every time the engine starts. For engines that start and stop once a minute or more, that would clearly be impractical. The fix would require tweaking the rules.